IVÁN CANDEO. HAY UN GOYA EN LA SOPA

30.04.22 > 07.22

HAY UN GOYA EN LA SOPA

by Iván Candeo

Alarcón Criado presents the second solo exhibition of Iván Candeo at the gallery, entitled “Hay un Goya en la sopa”. It’s based on the existence of a number of significant paintings attributed to the artist Francisco de Goya, that were acquired as original paintings by private collectors or sold in second-hand markets as authentic works by the Spanish painter. It was a scenario that became common all over the world, especially in France, Italy, and Austria, as well as in Spain and Venezuela.

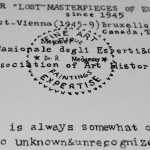

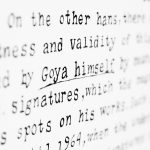

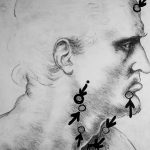

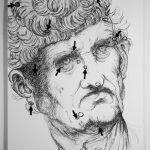

Iván Candeo refers to the strategic means by which experts, journalists, critics and collectors took for granted the story of the presence of Goya’s paintings in Venezuela. He is interested in the process of identifying graphics as “micro-signatures” and the subsequent certification of the paintings.

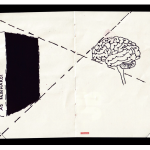

The exhibition brings together a series of drawings, photographic images and paintings in which elements typical of the apparatus of legitimization of works of art (legal documents, press articles, infrared reflectographies, arrows and signatures related to the Goya paintings in Venezuela) are stripped of validity and scientific evidence, replacing the utilitarian function that images have within the authentication process with a more symbolic one, with which to identify some distinctive features of an era and context. As Iván de la Nuez demonstrates in the text that he dedicates to the exhibition, “Goya is a state of mind of Western culture, the recurring adjective that best defines its consternations”.

The show concludes with an installation of Chinese ink drawings on pages from a 2020 planner, alongside the piece titled Un dólar. As in the works dedicated to the Goyas of Venezuela, this piece deals with the fluctuations that take place in the artistic field regarding material, monetary and symbolic value.

WHAT THEN?

A text by Iván de la Nuez

When Andy Warhol painted his portrait of Mao, he removed the wart from his face. As if this Photoshop exercise, avant la lettre, was enough to wash away his horrors. As if the facelift would be enough to melt the cultural revolution in a Western society permanently willing to bid for the portraits of the Supreme Leader, all the better if they were already stripped of that great little spot.

Recently, the Venezuelan artist Iván Candeo (Caracas, b. 1983) has been considering this exercise of wiping the slate clean. Sometimes, from his own mediations on a bygone history of art: Tinguely, Reinhardt, Malevich, Turner, Mondrian. AT other times, he adds the removed wart to the faces of other individuals from more recent political history: Cuba’s Díaz Canel, Nicaragua’s Ortega, Venezuela’s Maduro (affirming their brotherhood by placing the Chinese dictator’s protuberance on the chin, the moustache area, or the forehead of these individuals).

These visual essays are ultimately working tools – tools with which to investigate hypothetical stories about the skull of Romulo Gallegos, the link between image and exile, or icon and fetish, the act of looking in order to be looked at, the position of the eye in painting, and those objects that can never be lost sight of. Every once in a while, Candeo takes on the task of destabilising the parameters of this instinctive landscape, in order to ask the question, “What then?”

And so, with all these tools, it is possible to make way for a more ambitious and “showable” experiment. Such is the case of Goya’s presence in Venezuela. It is a plot that gave rise to a book of the same name, published in English (1993) and written jointly by Arnold Zingg, Robert C. Lespinasse B. and Rolph Z. Megdessy (the latter one of the most renowned forensic experts of the art world in the 20th century).

We know almost everything there is to know about Francisco de Goya y Lucientes. That he was born in Fuendetodos (1746) and died in Bordeaux (1828). He had a long life, especially by the standards of the time. And since his death, he has not ceased to afflict us with an influence that is rekindled in spurts.

Since the post-mortem period, we also know that in Guernica, Simon Schama discovers Picasso’s obsession with the Aragonese master, while Gombrich perceives some of his paintings as the J’accuse! of art. In Regarding the Pain of Others – The Disasters of War, Susan Sontag does not hesitate to describe his work as a direct antecedent of documentary photography.

It is also known that José Ángel Valente is dazzled by the double profile (Impressionist and Expressionist) of Goya’s legacy. The Chapman brothers went so far as to first purchase, and then alter the etchings that were discontinued due to his death. Spain honours its best-known film awards with his surname, an art that has not been alien to his genius. And not only for the films that have been dedicated to him, but also for his impact on the visuals of Luis Buñuel, Alfred Hitchcock, Carlos Saura, Tomás Gutiérrez Alea and Milos Forman.

Goya is a state of mind of Western culture, the recurring adjective that best defines its consternations. There is no culture in this hemisphere that resists “applying” it, nor “national” art that does not have its own particular versions of the Goyaesque.

For all these reasons, the umpteenth verification exercise of his “Venezuelan” paintings is of little interest. In fact, if they were forgeries, they would not be so because we do not have meticulous investigations, but precisely because we have them.

After all, when researching Goya’s connection with Latin America online (and Venezuela in particular), the most overwhelming result does not refer to the painter, but to the canned goods. A link to those Goya cans that, on both sides of the Rio Bravo, Latinos consume en masse. Those products that -from beans to sweet potato, to the sauce used to marinate pork- also indicate our relationship with romanticism. If the painter Goya is the sum of a collector and his wealth, the Goya product is the sum of the popular classes that do not require any link with art to pass the seasoning brush over a leg of pork or a turkey. For the former, it is a matter of honour. For the latter, it is a matter of the oven.

In the first instance, the Chapman brothers stand out. In the second case, Iván Candeo. One, by signing Goya’s work itself. The other, using the supposed “micro-signatures” of the painter to serve as an appetiser to his Venezuelan cooking of the Goyaesque.

Of course, they both alter Goya’s work, but their operations are set in opposition. The Chapmans can afford to buy the unfinished engravings and then act on them to establish their fiction on a real, though unfinished, work. Candeo, on the other hand, acts on a dubiously completed work until it becomes an unfinished truth. The Chapmans place Goya in a Disney aesthetic, Candeo turns our Disney reality into several possible Goyas. The Chapmans colour the darkness while Candeo knows, with Bataille, that darkness does not lie. That being dark is a way of being Goyaesque. That it is not necessary to paint over it but to let oneself be subsumed by its black holes.

The fact that remains is that the Chapmans resort to rehash in the same way that Candeo opts for asado. Chapman’s Goya enters through the eyes, Candeo’s enters through the mouth (through the vast oral tradition of books, articles, documents that reference his Venezuelan paintings). One presents himself as an iconoclast, the other as an iconophage. In the Chapmans, authenticity is not discussed, whilst Candeo places authenticity under suspicion.

When the first world practices appropriation, it always ends up presenting the result as original. When we practise it in Latin America, no matter how original we are, the final result always appears as a copy. It is a mere question of aesthetic geopolitics.

In this project, Iván Candeo takes us back to the processes through which experts, journalists and critics took for granted the history of Goya’s paintings in Venezuela. Even the history of Venezuela in Goya. Because, apart from his own demons, the artist cannot resist Bolivar (like his Peruvian contemporary José Gil de Castro).

In the end, the Goya of this exhibition contributes to the main movement of our time, which is inertia. It is a truth that Iván Candeo has worked on conscientiously. There is his self-titled work, Inercia (2009), a video in which a brave Venezuelan cyclist pedals on his static bicycle, trying to reach, unsuccessfully, the Bolivarian ideal. And here and now, with this Goya who hides his signature in Caracas as Warhol hid Mao’s wart in New York.

There are artists for whom the countercultural inhabits ideology, the city, morality, and money. In Candeo, counterculture takes place in time. Like an alternating current in the tide, an out-of-tune rhythm, an object out of place.

Thus, there is no room here for the nostalgic question of uchronia. What would have happened if…? Candeo prefers to create the event, establish the coordinates for things to happen and, already on the fait accompli, launch his favourite question.

“What then?”