Nicolas Grospierre. Heliosophia

NICOLAS GROSPIERRE

Heliosophia

The ancient Greek believed that Helios, the god of the sun, rode a fiery chariot through the sky, in this manner illuminating the world. However, when Helios let his son Phaeton lead the carriage, the inexperienced rider lost control over it, threatening to crash on earth and destroy the world. Zeus had to strike Helios’ chariot, killing Phaeton by the same token.

As is often the case, Greek mythology provides an accurate yet simple narration to apprehend man’s relation to the world around him. Echoes of this story are found in Nicolas Grospierre’s latest exhibition at Alarcon Criado: Heliosophia.

Composed of two distinct yet interdependent parts, Heliosophia brings forward works which develop an ambiguous relation to the sun, and light in general, as a creative means, but also perhaps as a destructive agent.

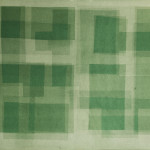

The first set of works, Heliographia, are abstract geometric compositions which seem to have been drawn on large velvet canvases. What looks like a print is in fact the direct action of the sun over several months. During this time, lightproof caches were placed over the velvet, and periodically moved, the sun burning out the exposed parts. It is a kind of photography without paper, without film, without camera even, the sun being the sole creative power.

Heliopolis is a set of photographs of modernist buildings from different parts of the world, whose common denominator is that they all have been destroyed, each time for different and specific reasons. However, the prints are tricked. Their photographic process has purposefully not been fixed, in such a way that when shown to the public, i.e. when exposed to light, they begin to black out. Here the sun is a destructive force, erasing structures which have already been torn down.

However, and upon closer examination, things are not as simple as they seem. Both works provide canny examples of the paradox of creative destruction, i.e. when the symbolic capital of the destruction of an object is greater than its material value.

One may indeed consider that the Heliographic compositions are in fact, from a technical point of view, the deterioration of an originally virgin piece of velvet.

On the other hand, the Heliopolis photographs are probably more than a simple set of images. One may indeed venture that it is their very fragile nature, their self- destructive quality – that the more one looks at them, the more they become difficult to perceive – which provides a truly genuine artistic experience.

Ultimately, Heliosophia is therefore not only about the sun, but about the complex and intertwined relation between the creative and destructive processes at work in any manly work.