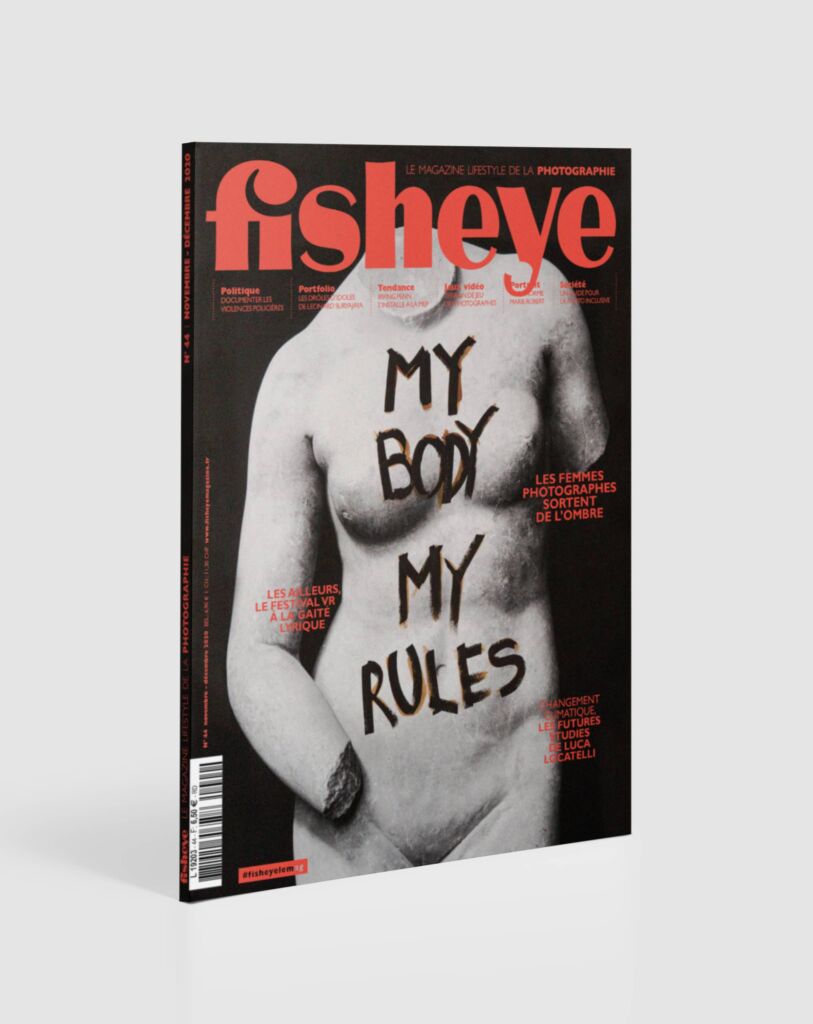

IRA LOMBARDIA I ELLES X PARIS PHOTO

A circuit dedicated to women photographers

A curation by Karolina Ziebinska-Lewandowska

Within the scope of the political campaign they lead in favour of the visibility of women photographers, the Ministry of Cultural Affairs has presented, over the last three years and in association with Paris Photo, a dedicated circuit: Elles X Paris Photo.

This year, to make up for the cancellation of the 2020 edition of Paris Photo at the Grand Palais due to health restrictions, the circuit is going digital: ellesxparisphoto.com.

Karolina Ziebinska-Lewandowska, curator of the Centre Pompidou’s Photography Center, took on its curation. To do so, she gathered around 40 women photographers – young, experienced, unknown, or whose careers have marked the history of photography.

Organised in five themes – luminous images, dreamt images, transformed images, militant images and testament images – the project builds imaginary bridges, highlighting the proximity between generations, sensitivities and aesthetic choices.

This website presents all artists from the circuit, including around 30 photographers interviewed on their status as women artists, their commitments, their inspirations. For ten of them, like Ira Lombardia there is a filmed interview in addition to their words. The website also presents infographics on women in photography in France, using updated numbers from studies from the Ministry of Cultural affairs: salaries, professions, studies, prizes, editions, presence in fairs, collections, exhibitions and festivals.

Last year, Paris Photo only counted 25% of women among the exhibited artists. Elles X Paris Photo, through this digital track, is fighting for a better representation and recognition of women photographers in the artistic field.

Elles x Paris Photo is a project carried out at the initiative of the Ministry of Culture, in partnership with Paris Photo and Fisheye Magazine, with the support of Women in Motion, a programme by Kering created to highlight the place of women in arts and culture

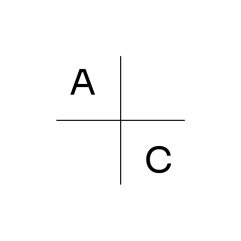

IRA LOMBARDIA

2018

Impudens Venus. The Proclaimer III ( Muy Body my Rules)

Acrylic on printed natural pigments on bamboo paper (290gr)

84 x 64 cm

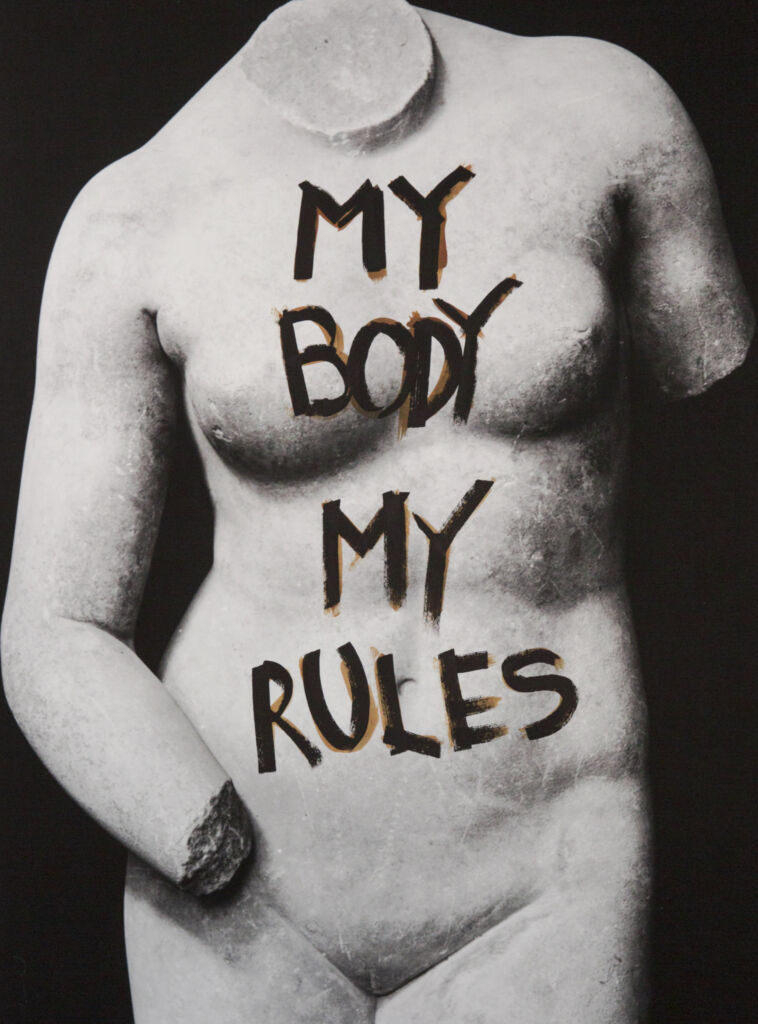

IRA LOMBARDIA

2018

Impudens Venus. The Proclaimer IV ( Not an Object)

Acrylic on printed natural pigments on bamboo paper (290gr)

84 x 64 cm

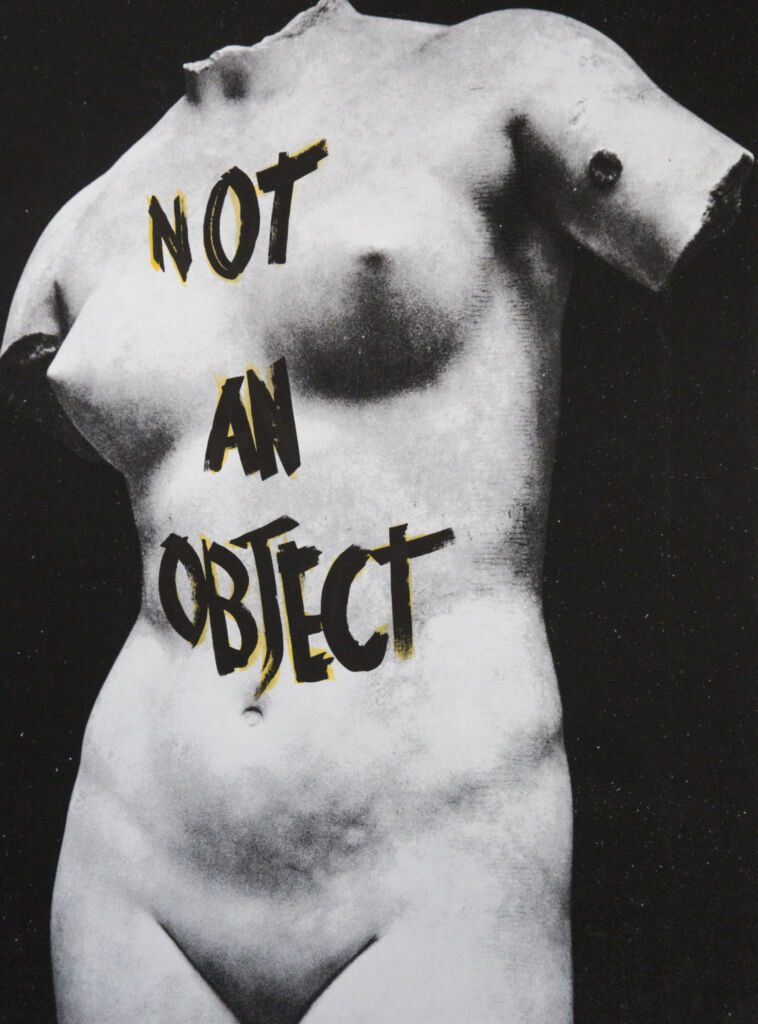

IRA LOMBARDIA

2018

Impudens Venus, The Proclaimer II (Fuck your Morals )

Acrylic on printed natural pigments on bamboo paper (290gr)

86 x 61 cm

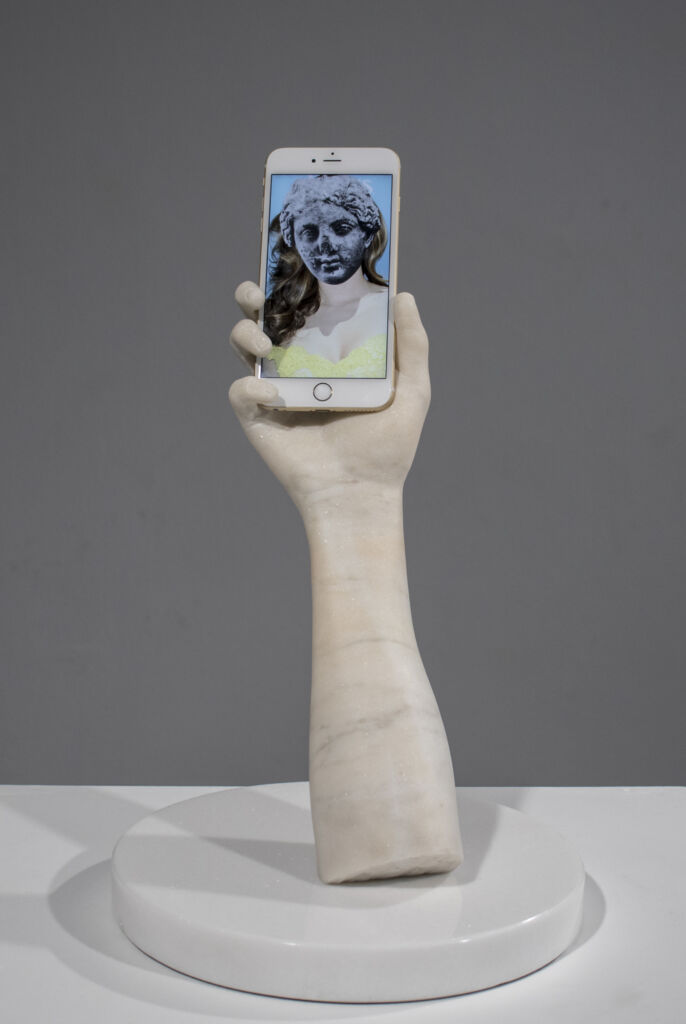

IRA LOMBARDIA

Swipe, Tap, Pinch (Venus). Neo Gods & Hyper Myths

2019

Video-sculpture. Marble and single channel video 2´33. Played on Iphone 6 Plus Gold.

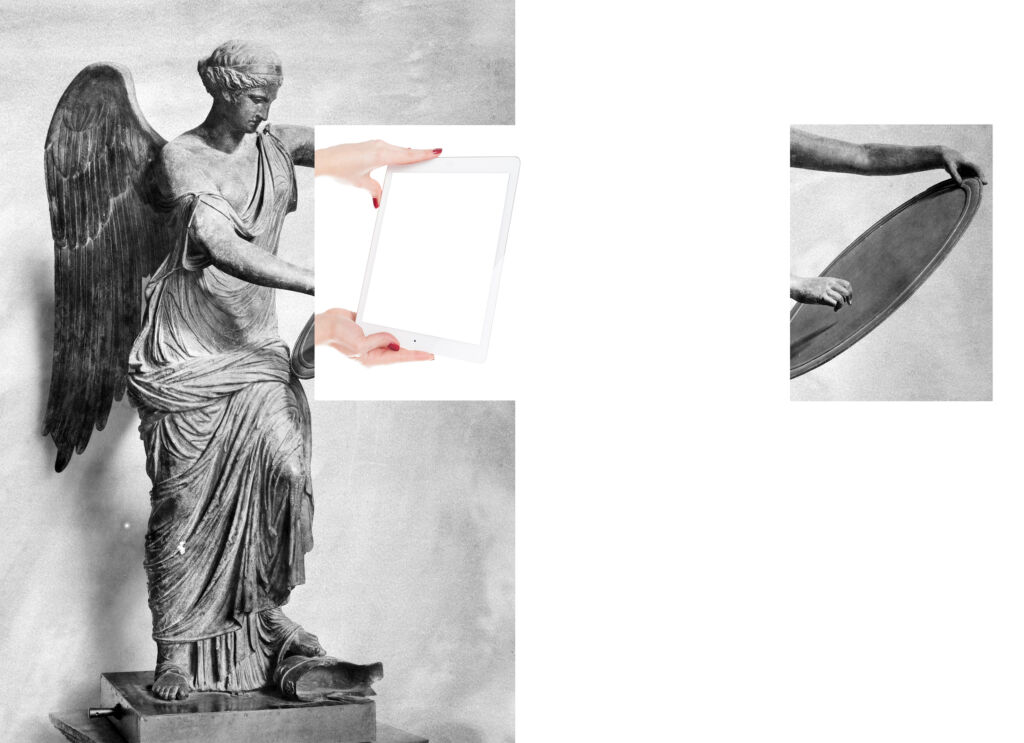

IRA LOMBARDIA

Venus with tablet. Neo Gods & Hyper Myths

2019

Natural pigment print on passpartout and on cotton paper

45 x 62 cm

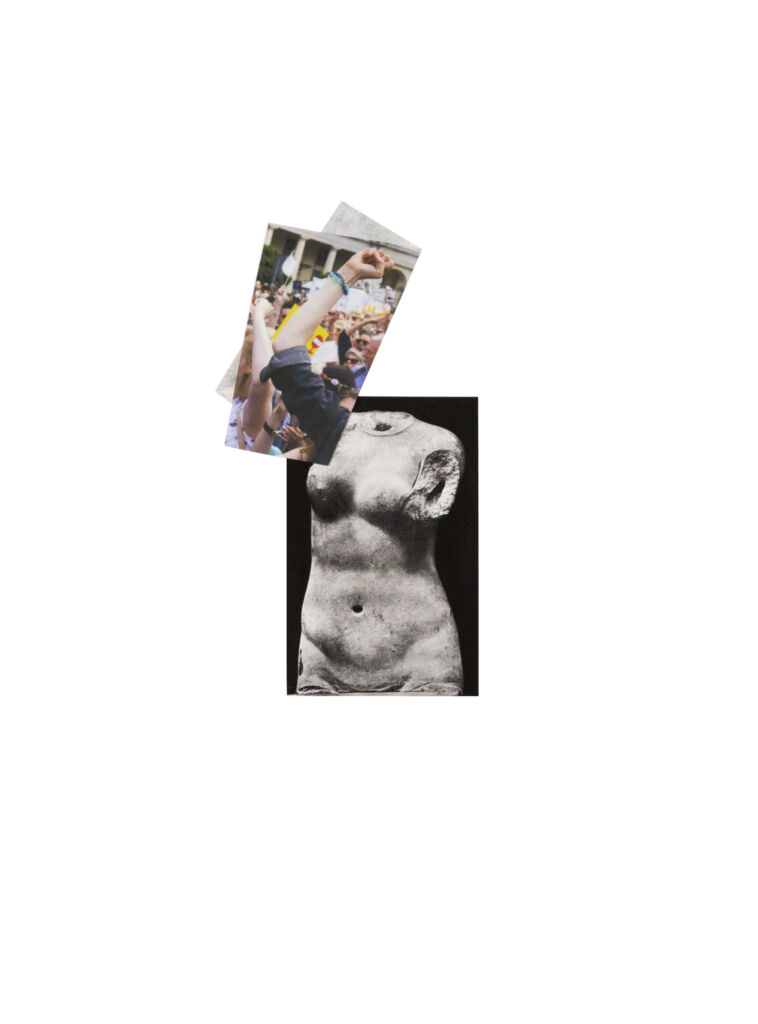

IRA LOMBARDIA

Impudens Venus X. Neo Gods & Hyper Myths

2020

Collage. Natural pigments on bamboo paper and kozo paper.

61 x 76 cm

IRA LOMBARDIA

Impudens Venus XI. Neo Gods & Hyper Myths

2020

Collage. Natural pigments on bamboo paper and kozo paper.

61 x 76 cm

Interview with Ira Lombardia. ELLES X Paris Photo 2020

LES FEMMES PHOTOGRAPHES SORTENT DE L’OMBRE. Fisheye Magazine #44. NOV-DEC

How did you become a photographer? Would you define yourself as a one?

My first encounter with photography was pretty amateurish. As many of us, my first contact was at home. I used to have a toy camera, and I loved to play with it. It could not even make images, but I was engaged in the act of taking photographs.

My father had some cameras at home. I still preserve a Polaroid camera and one of the first Sony digital cameras that was out in the market. I started to take photographs in a pretty natural way. At some point, in the university, I decided to learn more about photography and took photos of my family and friends. I never thought at that point that I would work in something related to art or photography… Which is why no, I do not consider myself as a photographer. I’d feel more comfortable with the “visual artist” label if I had to pick one.

What drives you as a photographer?

I barely take pictures… I’m not interested in taking photos, I’m more interested in how photography is produced, distributed and consumed, in the dynamics, in the flow, in the invisible part. I’m also interested in the meaning of images working as a group, as a cluster, in the gaps, the interstice between them.

In 2012, I decided to remove all the images from my website and commence a symbolic Visual Strike. For a thousand days people would only find a text explaining this lack of images. The commitment of not distributing any image brought me the opportunity to understand my photographic production in a new way. Since then, I have been interested in all the facts surrounding photography that are not the image itself. For me, photography is not about the visual content, it is about much more. I’m interested in working with the idea of dematerialization, to discuss issues that revolve around contemporary iconic super-habit and the impact of seventies appropriation on the dominant digital visual culture.

Do you think there is such a thing as a ‘woman’s gaze’ in photography? Is this something you can relate to?

I know the term can be controversial. As a woman, being defined by our gender can feel reductionist. Many prefer to be considered for their work rather than for the fact of being a woman. In one hand I feel that way, but in the other hand I feel comfortable with the idea of the “female gaze” as an artist. Many female artists became popular during postmodern criticism creating bodies of work that critique the “male gaze”. Artists such Barbara Kruger, Martha Rosler or Sherrie Levine use appropriation to let us think of images in a different way, they invite us to rethink those images, and their impact on art history is enormous. I feel in debt to that female gaze.

Has being a woman influenced your work as an artist in any way?

I am not sure about it, I could not imagine what would happen if I identified myself with a different gender. This is a good question…What I know is that I find it very odd, when I apply to an art contest, that they keep asking me whether I am a woman or a man… Does it matter at this point? Are there only two options? Why do they keep asking this? My inquiry probably implies some answers to your question.

Do you live off your art?

I do now. The balance between academics and my artistic practice works for me – I’m also an adjunct instructor at Syracuse University in New York. But I did not make real money with my art until I was almost 40 years old. Working with Alarcon Criado Gallery has made a real difference. Being an artist is a long-term career… I do not know any artist who decided to work in art because of the profit. You do it for other reasons and it implies big sacrifices. We are the last romantics of capitalism!

Which authors have inspired you? Are there any women photographers among them?

In my work I quote, use and rethink many works from other artists… The list is huge!

In addition to those I have already mentioned, there are many women artists that are fundamental to my practice. I could add names such as Dora Maar, Yoko Ono, Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Concha Jerez, Hito Steyerl, or Isa Genzken. And also, men artist such as Marcel Duchamp, John Baldessari, Joan Fontcuberta or Nacho Criado. Important theorists such as Lucy Lippard, Rosalind Krauss, Susan Sontag and Rosi Braidotti have had a huge impact on my practice. Art and theory made by others inspire me constantly, and I enjoy being a beholder and a reader so much.

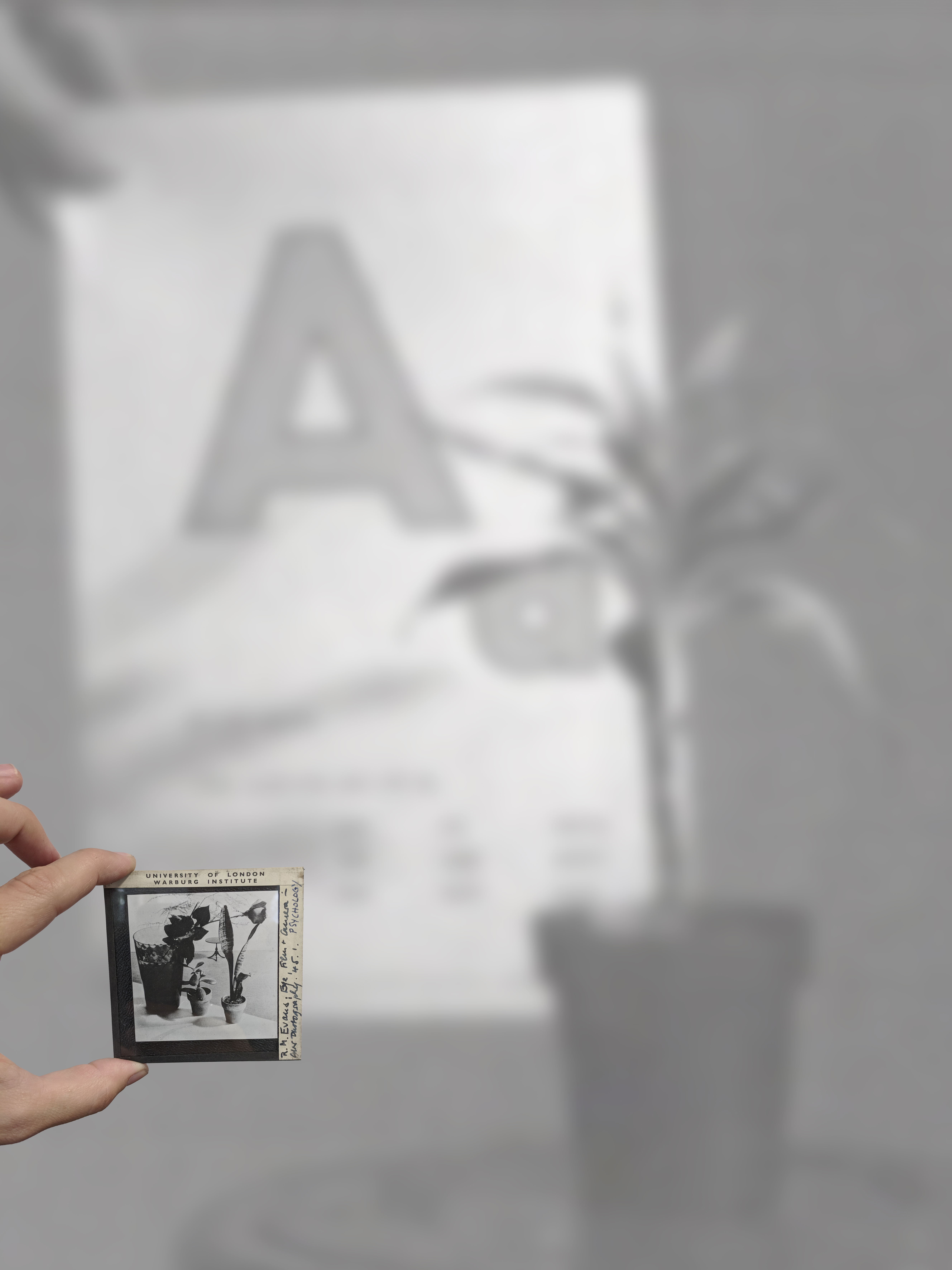

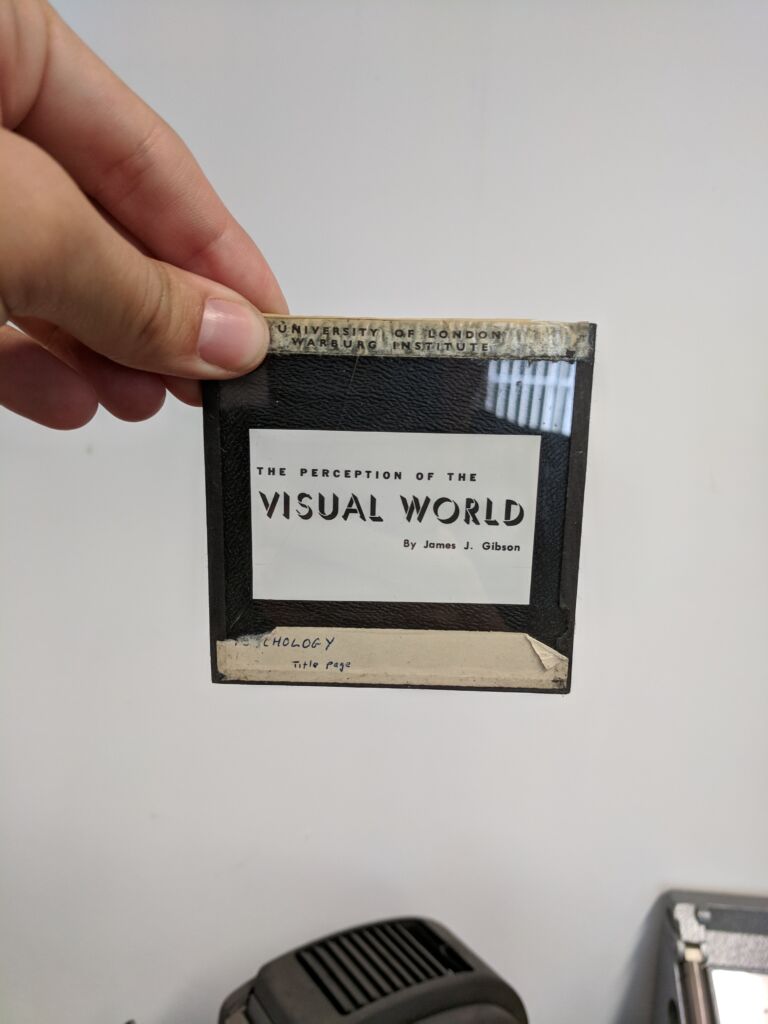

NEX PROYECT I SPEECHLESS (The Perception of the Visual World)

Slide, Institute Aby Warburg, London, 2018

In 2018, at the Aby Warburg Institute in London, I discovered a metal filing cabinet that contained numerous glass transparencies. Diagrams, drawings and photographs appeared on the slides that made reference to topics such as proportion, psychology or art. Without an established order, or any documentation and even with different sizes I was finally able to connect several images that seemed to refer to the same lecture.

The first slide reproduced the cover of the book “The Perception of the Visual World”. The manuscript, work of the American psychologist James J. Gibson, was published in 1950, and actually the book was at the Warburg Library. The text raises a disruptive and experimental thesis on the way we perceive images, a critical proposal with the dominant idea of cognitivism. This line of research would be known as “visual ecology”, and Gibson was the highest representative. Many of the book’s photographs were in fact reproduced on the glass slides that I found at the Institute; in addition, there were also other images on art history or even a couple slides that looks like “memes” that did not appear in the book and that were presumably intended to introduce a stroke of humor to keep the audience’s attention. There were also two slides referring to a second book, Eye, Film and Camera in color Photography, by R.M. Evans, and an extra one from the same author but different book, “Introduction to color”.

Despite having the books itself and handwritten notes on each of the slides, there was no way of knowing which was the speech that ordered and connected those images: there was no numbering or established order, and without any recording or phonographic file was impossible to know. It was an anomaly, a “speechless” lecture.

Was the conference a summary of Gibson’s book or was it a critique of his controversial work? Was it Gibson himself who gave the talk? Or was it Gombrich or maybe Gertrud Bing? How could those images make sense? The only thing that seemed clear to me is that the materiality of these slides printed on glass paradoxically conflicted with the immaterial nature of a lost speech, with those forgotten words, with an extinct discourse that once gave them meaning seven decades ago.

That conflict, that tension between the objectual and the immaterial, between the document and the referent, between images and words, between photography as an index and language as a structure, not only spoke of photographic nature, but of how photography has served as a discursive backing for numerous artistic practices.

My investigation materialized in a series of 12 artworks. In each of them, in a glass case, two images are put into dialogue: in the foreground, printed on glass, we can look at a life-size reproduction of the photographs I took at the Warburg Institute, where my hand holds a slide. In the background, we glimpse blurry images. Those are fragments of photographic documentation of dematerialized art practices from the seventies, where the photographic or audiovisual record was the only part that remained.

The discursive and iconographic associations between images, the distance among them, the opacity and transparency make up a visual discourse devoid of words. An invisible speech, constructed through pictures that navigates from the physicality of the image to the dematerialization of art, projecting analogies and conflicts.

DOSSIER SPEACHLESS

IRA LOMBARDIA

Man, hare, dog, bird. Speechless (The Perception of the visual World)

2020

Impresión UV sobre vidrio e impresión pigmentada sobre papel

60 x 40 cm

IRA LOMBARDIA

Fog. Speechless (The Perception of the visual World)

2020

Impresión UV sobre vidrio e impresión pigmentada sobre papel

60 x 40 cm

IRA LOMBARDIA

Gramatica. Speechless (The Perception of the visual World)

2020

Impresión UV sobre vidrio e impresión pigmentada sobre papel

60 x 40 cm

IRA LOMBARDIA

Survey. Speechless (The Perception of the visual World)

2020

Impresión UV sobre vidrio e impresión pigmentada sobre papel

60 x 40 cm

IRA LOMBARDIA

Filter. Speechless (The Perception of the visual World)

2020

Impresión UV sobre vidrio e impresión pigmentada sobre papel

60 x 40 cm

IRA LOMBARDIA

Plants on pots. Speechless (The Perception of the visual World)

2020

Impresión UV sobre vidrio e impresión pigmentada sobre papel

60 x 40 cm

IRA LOMBARDIA

Seated Man. Speechless (The Perception of the visual World)

2020

Impresión UV sobre vidrio e impresión pigmentada sobre papel

60 x 40 cm

IRA LOMBARDIA

Venus. Speechless (The Perception of the visual World)

2020

Impresión UV sobre vidrio e impresión pigmentada sobre papel

60 x 40 cm

IRA LOMBARDIA

The Pointing Instrument. Speechless (The Perception of the visual World)

2020

Impresión UV sobre vidrio e impresión pigmentada sobre papel

60 x 40 cm

IRA LOMBARDIA

Parcel. Speechless (The Perception of the visual World)

2020

Impresión UV sobre vidrio e impresión pigmentada sobre papel

60 x 40 cm

IRA LOMBARDIA

Raise. Speechless (The Perception of the visual World)

2020

Impresión UV sobre vidrio e impresión pigmentada sobre papel

60 x 40 cm

IRA LOMBARDIA

Stairway. Speechless (The Perception of the visual World)

2020

Impresión UV sobre vidrio e impresión pigmentada sobre papel

60 x 40 cm